Learning about React hooks and state - Part 2: Building a custom input

2021-12-29

This is Part 2 of a two-part tutorial on React hooks and state. Part 1 goes over basics of application state, as well as a first React hook: useState.

The final version of the code for this tutorial is available on CodeSandbox:

In this section we're going to modify the OtpInput component to make it look and behave differently to users, while keeping the same props API exposed to the outside. The end result is that an OtpInput instance will render multiple HTML input elements, and each one will be able to take in one digit. Here's the first iteration of that:

You can confirm by comparing the two previous sandboxes that we didn't have to change any code at all in App.js. The props still work the same way, and the disabling/enabling of the submit button works the same way as well. However, our custom OtpInput component now has much more complexity. Most of the logic is encapsulated in the handleValueChangeForIndex function. If it receives an input for a box (position) that can't be changed, then it doesn't change anything. You can try the component by manually focusing into each input field and typing one number. You can also remove digits one by one, manually.

Next, let's make the component more user-friendly by automatically focusing on the next input field after the user types a digit, or the previous input field if they delete a digit!

Adding side-effects with useEffect

In this section, we're going to want to focus on one of the input boxes after the value of the OTP code has changed. Focusing on an HTML input is done by calling its .focus() method. Calling this method is referred to as a "side-effect". Think of a side-effect as a "function that doesn't compute anything". You're already familiar with one such function, console.log(). The console log function doesn't compute any values, it just "does something". Printing to the console is called a side-effect, and so is focusing on an input.

Since the value that we want to use to execute this side-effect is coming down from props -- specifically the otpCode prop -- then what we want to do boils down to "we want to execute a side-effect in a React component as a result of a change in props (or state)". And that's exactly what the useEffect hook is intended for. useEffect takes two parameters:

- a function to execute -- this is the so-called side-effect. It can involve logging to the console, focusing an input, making an API call to a third-party server, etc.

- an optional array of "dependencies": the values in this array will be checked on every render, and if one of them has changed, then the function passed to that

useEffecthook will run again. these values are either direct props or state, or values computed from props and state. if the array of values is empty, then it never changes, so the effect will only be run once for each instance of the component. if there's no array passed touseEffect, then the effect will run on every render.

Let's look at a few examples of useEffect using the most basic side-effect ever, console.log:

If you load the sandbox and remove the last digit of the second input box, you'll get the following sequence of console.logs:

This is called on every render of the instance. This instance uses 5 digits.This is called only once per instance. This instance uses 5 digits.This is called when the code changes. New code: ""This is called on every render of the instance. This instance uses 6 digits.This is called only once per instance. This instance uses 6 digits.This is called when the code changes. New code: "123456"This is called on every render of the instance. This instance uses 5 digits.This is called on every render of the instance. This instance uses 6 digits.This is called when the code changes. New code: "12345"

And here's what the calls to useEffect do:

-

The first effect is executed on every render.

-

The second one is executed only once per instance, BUT since it uses the prop

numDigits, we get an eslint warning in the code:React Hook useEffect has a missing dependency: 'numDigits'. Either include it or remove the dependency array. (react-hooks/exhaustive-deps)What eslint is telling us here is that we're running an effect that uses a variable, but we won't re-run that effect if the variable's value changes. In this case that's exactly what we want to do, so we're fine.

-

The third effect has a dependency array with

otpCode. This means that it'll fire on the first render, but also every timeotpCodechanges.

You'll notice that the first effect, which fires on every render of the instance, is firing twice for the first OtpInput, even if we're not changing its value. Why is that? When we change the value of the second OtpInput, we're changing a state in App, so the whole App has to re-render. This means both instances of OtpInput are being re-rendered. Since the first instance will output the same set of React Elements, then React won't have to change anything in the DOM for that instance. However, if we're sure that this component will render the same when passed the same props, then we can wrap it with a React.memo. While React.memo isn't a hook, it's useful to mention it here: it will instruct react to "memoize" (remember) the output of a component for a given set of props. If a re-rendering of a parent component -- App in our case -- ends up passing the same props to a memoized component's instance, then React will short-circuit the rendering of that instance. This can sometimes be much faster than re-rendering the instance only to realize that nothing has changed.

Using useRef to keep track of a value that's not used for rendering

One of the useEffects we used in the previous section is called with otpCode as its dependency array. It fires on the first render and every time otpCode changes after that.

If we were to use this useEffect to focus on the next input box, then we'd have a problem: we'd also call a .focus() on the initial rendering, before the user has had the chance to input anything. We can attempt to fix this in the following way by introducing a state variable to check if we're on the first render:

const [firstRender, setFirstRender] = useState(true);

useEffect(() => {

if (firstRender) {

setFirstRender(false);

} else {

console.log(`New code: "${otpCode}"`);

}

}, [otpCode]);

On the first time this effect is called, it'll just change the firstRender state to false. Then on subsequent renders, it'll console.log the OTP code value. While this seems to work, there are two issues with it:

- We get a warning from eslint, because we're using a value in the effect --

firstRender-- and it's not in the dependency array. If we added this value to the dependency array, then the first useEffect would change the value to false, which would immediately trigger a second execution of the useEffect withfirstRenderbeing false. We could simply choose to ignore this warning, but it's a sign that we might be doing something wrong. - More importantly, we've just introduced a new piece of state,

firstRender, which isn't being used for rendering at all:firstRenderis only being used in a side-effect. This is usually a sign that we're doing something wrong. State should only be introduced if it's required for the rendering. Otherwise, changing these values will cause un-necessary re-renders.

We can try -- but FAIL -- to fix these two issues by creating a global variable firstRender at the level of the module. This variable will be the same from one rendering to the next. We can check and modify the value inside our useEffect, and since the variable is in the module's scope, any function created in the module that closes around this variable will always be referring to the same variable.

If you try this sandbox by looking at the console, you'll see a few things:

- We're not using state anymore to keep track of the first render

- We're using a global variable, which doesn't need to be specified in the dependencies

- Since this variable is global to the whole module, it's the same value no matter how many instances of the component we're using! So the first

OtpInput'suseEffectcall will setisFirstRendertofalse, but then when the second instance gets rendered, the value will already befalse.

What we really need to keep track of this is a stable reference that doesn't change between renders, but is different for each instance of a component. This is exactly what useRef is for. A call to the useRef hook will create a box on the first render, and put any value we give in that box. The value is accessed using the .current property of the ref, and the box is mutable, so we don't need a "setting function" like we do for useState. We can just call myRef.current = newValue to change the value of the box. Changes to the value in that box don't cause re-renders -- if we wanted that we'd use a state instead. Here's how we'd modify our code to use useRef instead of a global variable:

Notice that the code now works exactly as expected: we initialize one box per OtpInput instance, with the value true. We change the value of the box to false on the first execution of the hook. Then on subsequent executions the box is false so we call console.log.

We can do even better than using a firstRender ref: why not store the "previous value" of the otp code? This way we can compare the current value -- otpCode -- and the previous value -- previousRef.current -- to create even more complex logic:

const previousOtpCodeRef = useRef(otpCode);

useEffect(() => {

if (previousOtpCodeRef.current.length < otpCode.length) {

console.log("You have added one digit from the value");

} else if (previousOtpCodeRef.current.length > otpCode.length) {

console.log("You have removed a digit to the code");

}

// Set the new value of the ref

previousOtpCodeRef.current = otpCode;

}, [otpCode]);

Here we initialize the box to have the same value as the initial otpCode. When the otpCode state is updated, our side effect is run: we check the new otpCode against the previous value, and run some logic. Then we update the box to the current value. This update to the ref won't cause a re-render, and that's good because we don't need one: we're only using previousOtpCodeRef in this effect, and not anywhere in the rendering. Now let's use this structure to focus on the correct input box depending on the change in the code!

Focusing on the correct input box when the value of the OTP code changes

The structure of the previous example will stay the same, only the effects themselves will change from console.log to input.focus():

if (previousOtpCodeRef.current.length < otpCode.length) {

// If we add a new digit, then we want to move to the next box

} else if (previousOtpCodeRef.current.length > otpCode.length) {

// If we remove a digit, then we want to move to the previous box. For convenience, we also want to select the value in the previous box to make it easier for the user to change it

}

To be able to focus on the inputs, we need to have references to their DOM elements. Normally we can do that by calling const inputRef = useRef(null) to create a new reference with a null value, then pass this reference to an element with ref={inputRef}. In our case however, we can't do that directly because we need multiple calls to useRef depending on the numDigits value. If we were to call useRef in a loop, and the number of digits were to change, then we'd have a different number of hook calls on different renders. Remember that React needs to know which hook call is which, and can only know that if we call the same number of hooks in the same order on every render. So we'll have to find another way.

Here, we can create a single reference: an array. We can store as many refs as we want in that array by creating them with createRef. createRef is NOT a React hook. It's simply a function that creates a box, but it will recreate a different box on every call to it. Since we're storing these references in an array created by useRef, we'll be able to keep them stable throughout the lifetime of the component's instance, this way:

const inputBoxesRefs = useRef([]);

for (let boxNum = inputBoxesRefs.current.length; boxNum < numDigits; boxNum++) {

if (!inputBoxesRefs.current[boxNum]) {

inputBoxesRefs.current[boxNum] = createRef();

}

}

return (

/// ...

<input ref={inputBoxesRefs.current[idx]} />

// ...

);

On the first render, we'll fill the referenced array with refs. On subsequent renders, we won't do anything because we'll be getting back the same array. Only if we get re-rendered with more digits, then we'll add more refs to the array. We can then use the refs in the array when rendering <inputs>, and again in useEffect when focusing on the correct input:

The interaction is still far from perfect, but it's already much better than before! Remember that we're making all these changes without changing our props API at all. Notice that we often have guards of the form if (inputRef.current)? That's because refs to React elements can sometimes be null: if a React element is rendered conditionally, then React will set its ref's .current property to null at times when it's not rendered.

Adding a ref with the useImperativeHandle hook

When we first started rendering DOM inputs, we saw that by getting a ref to a DOM input, we could extract its .value as needed. This allowed us to use DOM inputs in an uncontrolled way, but still access the value if needed. We can also make our custom OtpInput component accept a ref prop by using React.forwardRef. forwardRef isn't a hook, but it wraps a component in a way that the component can be passed a ref, and receive it.

Once a component receives a ref, it can mainly do two things to it:

- Most of the time, we receive a

refand just pass it down to a child component that we're rendering. For example, if we're building a UI library and creating a<TextField>component, we can choose to accept aref, and pass it down directly to the<input>that we're rendering insideTextField. - In our case, we want to expose our own API through the ref. We don't have any elements to pass down the ref to, but we'd like to allow a parent component to call functions that will have effects inside our component, or allow a parent component to retrieve the value in the case of an uncontrolled instance. For these cases, we use the lesser-known

useImperativeHandlehook. It allows us to create an API that can be used by a parent component. Here's an example:

In the final version of the component, linked at the top of this tutorial, we also add a value to the ref's API: this allows us to use the OtpInput component in an uncontrolled manner if we wish to do so.

There are many more improvements and changes we can make to the OtpInput component, and you're encouraged to personalize it as you wish. But in the next section, we'll see how we can make our code cleaner by creating re-usable hooks.

Cleaning up the mess: creating re-usable hooks

As a component's logic starts to get more complex, we quickly start dealing with a soup of hooks. These hooks are also mixed with rendering logic, which can make things even worse.

Thankfully, since hooks are just function calls, we can compose them into higher-level hooks that encapsulate their implementation.

Here's a first example. When creating the array of refs for our multiple input boxes, we have the following code:

// Create refs for the inputs

const inputBoxesRefs = useRef([]);

for (

let boxNum = inputBoxesRefs.current.length;

boxNum < numDigits;

boxNum++

) {

if (!inputBoxesRefs.current[boxNum]) {

inputBoxesRefs.current[boxNum] = createRef();

}

}

We can easily move this code to a function called useRefArray, put it in its own file, and reduce the number of lines of code in OtpInput by much:

// useRefArray.js

import { useRef } from 'react';

export const useRefArray = (numRefs) => {

const refs = useRef([]);

for (let refNum = refs.current.length; refNum < numRefs; refNum++) {

refs.current[refNum] = createRef();

}

return refs.current;

}

Then in our component:

// OtpInput.js

import { useRefArray } from './useRefArray' // instead of importing useRef from React

//...later during rendering, tada! one line of code

const inputBoxesRefs = useRefArray(numDigits);

Similarly, we can create a "previous value" effect hook:

// usePrevValueEffect.js

import { useRef, useEffect } from 'react';

export const usePrevValueEffect = (effectToRun, currentValue) => {

const prevValueRef = useRef(currentValue);

useEffect(() => {

effectToRun(prevValueRef.current, currentValue);

prevValueRef.current = currentValue;

}, [currentValue, effectToRun]);

}

// OtpInput.js

usePrevValueEffect((previousOtp, currentOtp) => {

// Run some logic based on changing otp codes

}, otpCode);

Using useCallback to prevent unnecessary value change detections in useEffects

One issue with the hook above is that the value of effectToRun will be different on each render, because we're creating a new function on each render. This may not be straightforward to a novice JavaScript programmer, so let's carefully review what's happening.

Aside: how === works in JavaScript?

Since useEffect compares values in its dependency array using the === operator, it'll be have differently based on the type of these values.

JavaScript recognizes different types of values: numbers, strings, booleans, null (null is a type where the only value is null), undefined (a type where the only value is undefined), objects, and functions. Notice that arrays aren't in that list? That's because arrays are just objects. Functions are objects too, but they're recognized as functions by typeof.

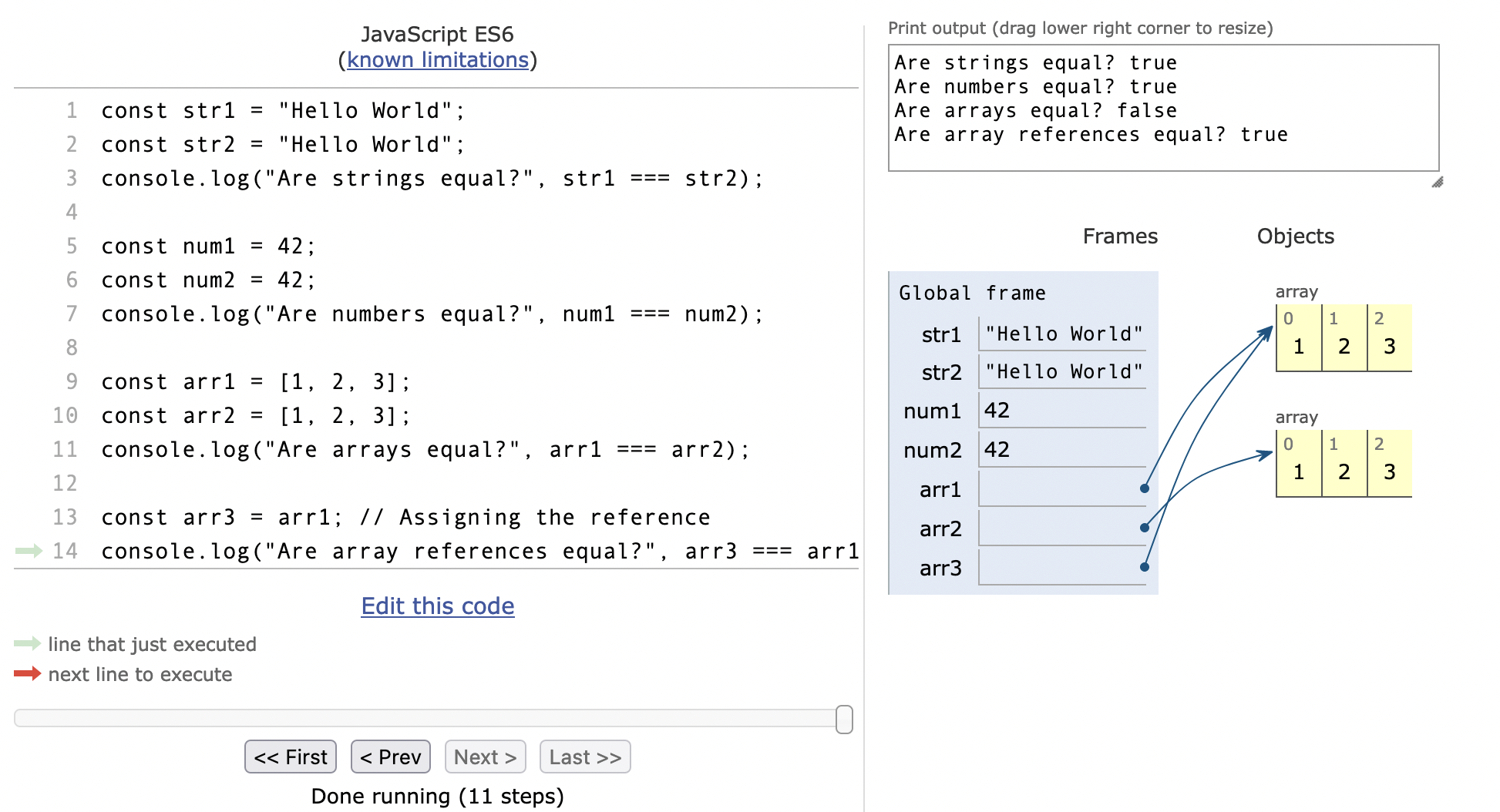

JavaScript treats some of the types as primitive types: strings, numbers, booleans, null, and undefined. The other types, objects and functions, are treated as references. The === operator compares primitive types litterally, and reference types using the object that they refer to in memory. This is best visualized using the following JavaScript Tutor simulator output. On the left is code that sets up different variables, at the top is the console output, and below it is a visualization of the values held by the different variables:

Note how numbers and strings are compared litterally, while arrays are compared by the arrows they point to (references). So are objects and functions.

Since a new function is being created on every render, even if the function is created with 100% exactly the same code, useEffect will be run even when it normally shouldn't run. Here's an example of that outside of our OtpInput setup:

If you change the value of the second input, you'll notice that loggerEffect is still being executed. That's because, even though input1 hasn't changed, loggerEffect refers to a new function reference: the function gets re-created on every input.

What we need is a way to re-create the function only when one of its external dependencies changes. That's exactly what the useCallback hook is for: it allows us to create a stable reference to a function between renders, by only having to define the dependencies of that function. Thankfully, our loggerEffect function doesn't have any dependencies: it only uses its arguments! So we can do:

const loggerEffect = useCallback((prevValue, currentValue) => {

console.log("INPUT1 CHANGE", prevValue, currentValue);

}, []);

If you do this in the sandbox above, you'll notice that the issue doesn't present itself anymore, since we have the same reference to the loggerEffect function every time.

Putting it all together

Looking at the OtpInput component as a whole, we can clearly see two parts there: the part that uses hooks to drive the logic of the component, and the part that renders the input boxes.

What if we wanted to take advantage of all the logic of OtpInput, but render different inputs, such as custom inputs from the MUI (Material UI) library for example?

One way to do this is to completely extract all the logic of OtpInput to a custom hook, and expose only what's necessary from that hook to drive the UI. Here's what it would look like:

In this sandbox, we have a separate useOtpInput custom hook. It accepts values that it uses to call the basic React hooks -- it could call other custom hooks as well, it's just function calls.

The custom hook then exposes only what's necessary for rendering: an array of props to be passed to inputs. As long as these inputs have a way to receive the props, then we can just spread them, and customize the rest to our liking. For example, we created a separate MuiInputBox component that re-uses 100% of the logic that was originally in OtpInput, with only a slight modification to how we render the UI.

The End...?

We've learned a lot in this tutorial. It's time to reflect on some of the things that we learned:

- React components can use state to drive the rendering of their UI

- State values should be kept to the essential. Two important rules are:

- Any value that can be computed from another state value should be computed

- Any values that is NOT being used to drive the rendering of a component shouldn't be a state value

- State can be created by calling the

useStatehook, which returns the current value of that state and a function to change the value (+ cause a re-render) - Multiple states can be created per component instance. The only thing that differentiates them is the order in which

useStates -- and other hooks -- were called. That's why every render of a component instance needs to have the same number of hook calls, and they must be called in the same order. No hooks inifs,fors,whiles, or array iterators. - Sometimes components need to fire off actions as a result of a change in their props or state:

- These actions are called side-effects, because they don't usually compute anything: they "do things" instead.

- These actions can be called by passing them to a

useEffecthook. useEffectneeds to know when to call these effects. The second parameter is an array of values. When any of the values in the array changes, the effect passed touseEffectwill be called again.- The equality of the values checked by

useEffectuses the JavaScript===operator. Strings, booleans, numbers,null, andundefinedall compare litterally. However, arrays, objects, and functions are compared using their reference. Among other examples, two empty arrays are not equal. Two functions created using the same code are not equal either.

- If we want a stable reference to a function, e.g. to pass it to

useEffect, then we need to create the function withuseCallback:useCallbacktakes an array of dependencies, and will re-create the function only if those dependencies change.- If a function only depends on its arguments and/or other stable references, then we can pass an empty array of dependencies to

useCallback, and we'll always get a reference to the same function

- If we want a stable reference to another value than a function, and that value doesn't drive the rendering of the component but is used in other places such as effects or event handlers, then we can create a box for that value using

useRef:useRefwill create a box on the first render, and place an initial value there- The value of the box is accessible using the

.currentproperty of the ref - The value can be mutated at will, again by accessing the

.currentproperty of the ref - Changing the value of a ref will not cause a re-render.

- Complex hook logic can be abstracted away in a custom hook:

- Thanks to developers like you, there exist tons of open-source libraries of custom, reusable hooks for integrating with various systems, or driving complex UI logic.

- Since these custom hooks don't do any rendering themselves, they can be re-used even more

- If no custom hook exists for what you're trying to accomplish, then you can easily create your own -- and open-source it! A custom hook is just a function that calls other hooks.

There are some hooks that we didn't cover in this tutorial: useContext,useMemo, and useLayoutEffect are only some of the other oft-used React hooks that you can learn about. What more, even with everything we saw about the hooks we did cover, there is plenty more to learn and experiment. In a future tutorial, we're going to see how to create and use type safe hooks with TypeScript. Meanwhile, go and build things with React hooks 🚀🚀